Relevant Anatomy and Physiology of Pediatric Patient:

The Airway and Respiratory System

Airway anatomy

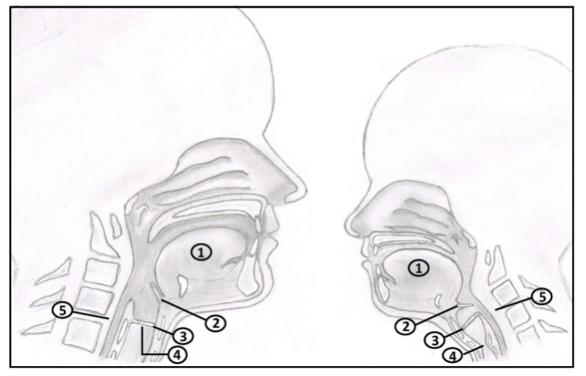

The neonatal upper airway differs from the adult airway in 5 significant ways:

- An infant’s tongue is larger in proportion to the oral cavity.

- An infant’s epiglottis is narrower and angled posteriorly over the glottic opening instead of parallel to the trachea as in adults.

- The anterior commissure of an infant’s vocal cords is attached inferiorly relative to the cord’s posterior attachments, instead of perpendicular to the trachea as in an adult.

- Traditionally, it is thought that in infants’ non-expandable cricoid cartilage is the narrowest part of the airways instead of the glottic opening as in an adult.

- The larynx sits higher in an infant, at the level of C3-4, as opposed to C4-5 in an adult. This creates the illusion of an "anterior larynx".

- Consequence: Greater risk of upper airway obstruction under anesthesia

- Consequence: Infant’s epiglottis must be lifted from below, during laryngoscopy to reveal glottis.

- Consequence: The endotracheal tube tip is more likely to be caught at the anterior commissure in infants and should therefore be advanced gently with rotation as needed.

- Consequence: Mucosal pressure from an endotracheal tube at the level of the cricoid is more likely to cause ischemic injury and/or edema. Therefore, one should use uncuffed tubes sized to provide a detectable leak for children ≤ 8 years old. If cuff must be used, then limit cuff pressure to < 20cm H2O.

- Consequence: More difficult to align oropharynx with trachea, therefore, optimize neck extension (i.e. with a shoulder roll) and do not put a pillow under the occiput.

Respiratory Physiology

Control of Respiration

In infants and neonates (pre-mature):

- Hypoxemia produces respiratory depression instead of activation.

- Periodic breathing (5-10s apneic spells) is common.

- Central apnea (≥15s or associated bradycardia/pallor/cyanosis) is present in half of premature neonates but rarely in full-term.

Respiratory Mechanics

The lung volume in early infancy is smaller relative to body size in adults but metabolic rate is double.

- Implications: Infants, and young children, desaturate faster than healthy adults once apneic.

Effects of Anesthesia on the Respiratory System

The pharmacology of anesthetic agents is reviewed elsewhere in this text.

- Inhalational agents: faster onset and washout as well as higher MAC requirement due to increased alveolar ventilation relative to FRC, a higher cardiac output and greater distribution of blood to vessel rich areas.

- IV agents: generally higher drug requirements by weight (e.g. propofol and opioids) due to greater volume of distribution.

The Cardiovascular System

Fetal and Transitional Circulation

Foramen ovale, ductus arteriosus, and ductus venosus shunt fetal blood, thus creating parallel left and right circulations.

At birth, placenta is clamped, systemic vascular resistance rises and the ductus arteriosus closes. Rising left atrial pressure closes the foramen ovale.

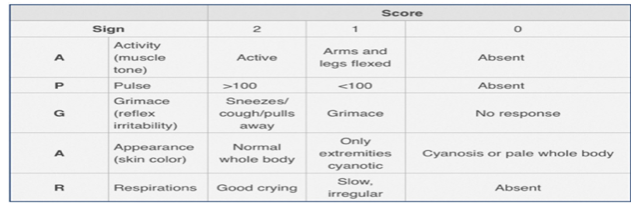

APGAR score:

- A quick assessment of neonatal health status at 1 and 5 minutes of life.

- 5 minute score < 4 is predictor of high neonatal mortality

Cardiac Function in Childhood

The developing heart of infants and neonates is stiffer and has limited ability to increase stroke volume. Therefore, heart rate has a significant influence on cardiac output.

Effects of Anesthesia on the Cardiovascular System

Immature heart is more sensitive to depression from volatile agents and bradycardia secondary to opioids.

Children are more susceptible to succinylcholine induced bradycardia therefore atropine should be prepared in advance.

Next page: Conduct of Anesthesia in Pediatrics